European elections: “A lot is at stake!”

6 May 2024

The EU faces enormous challenges: The elections will show how far it has the backing of its citizens. An interview with political scientist Berthold Rittberger.

6 May 2024

The EU faces enormous challenges: The elections will show how far it has the backing of its citizens. An interview with political scientist Berthold Rittberger.

Germany will cast its votes in the European elections on 9 June 2024. In the interview reproduced below, Berthold Rittberger, holder of the Chair of International Relations at LMU, talks about democratic control in the European Union and current domestic and foreign policy challenges.

Compared to other international organizations, the EU is quite unique in that it commands authority and competences in numerous policy fields.Berthold Rittberger

The European elections are held in early June: What part does democratic control play in the EU?

Berthold Rittberger: It plays an ever more important part. Compared to other international organizations, the EU is quite unique in that it commands authority and competences in numerous policy fields. That requires an exceptional level of democratic control, which is exercised, on the one hand, by the member states and the governments that are elected by their people. But there is also a second avenue of control: the European Parliament, which represents EU citizens directly. Through Parliament, every citizen in Europe has a say in democratically influencing and controlling the decision-makers in Brussels, in the Council and in the Commission.

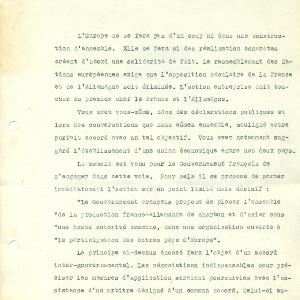

to integrate the production of coal and steel across national borders. In this letter, Schuman notified then German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of his plan. | © CC-BY-ND

Why is the EU responsible for so much today? When it began in 1952, it was only about the production and trade of coal and steel?

The objective of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was, indeed, restricted to these two sectors. Yet, the ECSC had a much wider objective. The aim was to safeguard peace and stability in Europe by offering Germany, which had brought such calamity upon the world, integration in an alliance on equal footing. At the time, for the project to be credible, nation states obliged themselves to devolve political decision-making powers to a supranational level, which was asking a lot from them. Seen from this angle, yes, Europe was an economic project. But one central goal was to integrate Germany and stabilize Western Europe vis-à-vis the Eastern Bloc controlled by the Soviet Union. Federalists’ dream of a United States of Europe and the obsolescence the nation state had already been abandoned by the end of the 1950s. It was the functionalists who won the day: Their view was that attempts to knit Europe more closely together must be made by addressing specific problems. The most obvious of these was to create a common market in order to stimulate economic development.

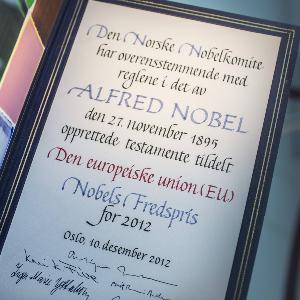

The Nobel Committee noted that the EU had turned a continent of war into a continent of peace. | © IMAGO / photothek / Ute Grabowsky

Today, the EU is far more than a common market. How did this come about?

The EU has deepened with each step toward integration, because every step of integration created new challenges that in turn had to be resolved by deeper integration.

The common market within which goods could move freely across borders was a step along the way to freedom of movement for workers. This implies that people who relocate within the EU came to claim social rights, which is why the EU has a social policy. A free market – albeit a tightly regulated one – took shape: There are common standards for consumers, healthcare and environmental protection, one reason being to prevent countries that lower these standards from gaining unfair competitive advantages.

Market integration also had a knock-on effect on other policy areas that, at first glance, have little to do with economic integration. If borders within the single market are removed, better protection is needed for external borders, as is closer cooperation between domestic law enforcement and police agencies across internal EU borders to catch criminals. The common currency, too, was created as a tool to advance economic integration. Yet, this necessitated a common fiscal policy, which the EU did not have. It was only after the euro crisis that a fiscal stabilization mechanism was created that provided the EU with some fiscal clout to react to macro-economic imbalances.

These days, the EU is often perceived in light of its crises. Why is that?

The euro crisis in 2008 was doubtless a watershed, but something in the quality of European relations had changed even before this point. Since the 1990s, what used to be predominantly an economic project had become a political project. This development was accompanied by questions about the very core of national sovereignty: the introduction of the euro, the greater attention paid to a common foreign and security policy, questions about asylum and migration policy. Increasingly, these issues politicized the process of EU integration.

The EU has become the object of public debate. And each crisis triggered further waves of politicization – waves that were also instrumentalized by Euroskeptic and nationalist-populist parties to mobilize people against the EU. Yet it is often overlooked, or deliberately not mentioned, that, although more and more functions have been devolved to the EU and although it now holds much decision-making authority, it often lacks the material and financial resources to operate effective crisis response policies. Without member states governments there would be no euro stability mechanism, no corona relief funds, no financial support for weapons deliveries to Ukraine, no solidarity mechanism for the distribution of refugees within the EU.

Although the EU is a major economic power, it carries little weight as a security policy actor on the international stage.Berthold Rittberger

Since 1979, it has been elected directly by citizens of the EU. | © picture alliance / imageBROKER | Daniel Schoenen

What challenges lie ahead of the EU in the coming years?

There are major challenges. Internally, there is the EU’s own ability to resolve problems. The member states must outfit the EU with the capacities to respond better and more actively to crises. This implies ramping up its material and financial resources. The second issue is foreign policy. Although the EU is a major economic power, it carries little weight as a security policy actor on the international stage. Right now, the war in the Middle East is highlighting what a hard time the EU has speaking with one voice. By contrast, when the EU Commission addresses economic and foreign trade issues, it speaks for all 27 member states.

Especially in the new geopolitical environment in which the USA is more inward-looking, the EU will have to close ranks much more tightly if it is to exert any foreign policy influence on the world around it. Ukraine is a prime example: On its own, the EU seems unable to do what is necessary to enable Ukraine to stand up to the Russian invasion. If the EU aspires to play an influential role in security policy, it must be able to think about its own security and defense policy apart from the USA. And it needs to find answers quickly. If it fails to do so, the EU will struggle to meet the challenges from emerging major powers, such as China, and revisionist powers, such as Russia.

Will new structures have to be created to do so?

On the one hand, we need to discuss the extent to which the principle of unanimity, which prevents the EU from responding quickly and resolutely to external threats, can be loosened in the context of foreign and security policy. At the same time, the EU’s member states must put the existing possibility of differentiated integration to better use. In other words, to move integration ahead on certain issues, you don’t always have to have all states going along at the same pace or blocking those who would advance.

European integration began with six countries. Today, the EU has 27. Do you see EU expansion as another of these challenges?

Yes, I do. And that has to do with the EU’s internal problem-solving ability. How large can the EU get? Many countries in the western Balkan region want to join, as do Ukraine and Moldova. The EU needs to be clear about how it can remain sufficiently agile to act within its existing structures if it has 30 or more members. Even where qualified majority decisions are possible, they are often difficult to come about. And where unanimity is required, as in foreign and security policy, it becomes even harder.

There is a lot at stake in these elections. The European Parliament has a say in deciding whether a country can accede to the EU. It plays a critical role in all economic matters and many of the future issues that concern us as citizens, such as climate change mitigation and migration policy.Berthold Rittberger

“The EU was created to make the nation states that emerged battered and bruised from World War II economically viable, and to give them a vision of stability that they, as sovereign states, could achieve only if they worked closely together. Since then, integration has advanced to a stage where it calls into question widely shared conceptions of national sovereignty. It is quite paradoxical: EU integration helped salvage the nation state, yet today some want the world to return to nation state-centrism,” says Berthold Rittberger. | © LMU / Stephan Höck

Why should EU citizens vote?

There is a lot at stake in these elections. The European Parliament has a say in deciding whether a country can accede to the EU. It plays a critical role in all economic matters and many of the future issues that concern us as citizens, such as climate change mitigation and migration policy. What Parliament decides when it has its say is defined by the upcoming elections. Euroskeptic parties will seek to prevent European solutions so that more happens at the level of the nation state. And if I, as a citizen, vote for either a more right-wing or a more left-wing party, that too has repercussions. For example, the European Parliament will likely support the Commission’s ambitious climate targets if the center-left has a majority after the elections. So, for anyone for whom mitigating climate change is important, the vote you cast in June is tremendously important. The same goes obviously for those who believe that climate policy measures are going too far and they vote a majority of right-wing and Eurosceptic parties into power.

And you will also go to the polls?

Obviously! When it comes to influencing the important policy issues of our day, those that concern so many people, this is probably a more important election than many of the others that lie ahead of us in Germany this year. We would be fools not to seize this opportunity.

Berthold Rittberger holds the Chair for International Relations at LMU’s Geschwister Scholl Institute of Political Science. His research addresses the dynamics of European integration and issues around democratic control. In the Beck series on Wissen (Knowledge), his book Die Europäische Union (The European Union) provides an introduction to the EU and how it works.

European Parliament: European elections 2024